Anna Murray introduces some of the music that will be enjoyed at the 2018 Annual Concert of the International Alliance for Women in Music (27th October, Dublin).

The International Alliance for Women in Music (IAWM) is an organisation with approximately 400 members, dedicated to promoting and encouraging the activities of women in music. Formed in 1995, the organisation promotes many aspects of women’s musical activities, from concert performances to musicological or journalistic work, and presents an annual concert each year of works selected from a call for scores.

With initiatives such as Sounding the Feminists gaining ground in the fight for equitable treatment in the music industry in Ireland – the IAWM has brought organisations and musicians together in the commitment for equitable programming, and entered into a multi-year commissioning and curation project with the National Concert Hall – it feels as if we are on the cusp of a change. There is resistance, and change is slow, but our music scene feels mobilised in a new, if hesitant way, like a jolt of static has been shot through us all, accompanied by the words ‘no more’.

Ireland may have some way to go yet towards representative equality – and diversity of all forms – in our musical life. Indeed, until recently, many organisations did not have representation guidelines or quotas (a contentious issue perhaps outside the scope of this article). One of the achievements of which I am most proud from my tenure as Secretary of the Association of Irish Composers was to conduct gender audits of our membership and projects, and to implement an official policy of a minimum quota of 30% of female composers, musicians, panellists etc. in the organisation’s activities, in line with membership, and goals to see this increase to 50%.

It feels particularly appropriate then that the AIC now moves forward with further initiatives under its new leadership, partnering with the International Alliance for Women in Music to present their annual concert in Ireland, and I am honoured to have a piece included in the selection.

We are all attempting to redress the balance, through female composer-only concerts, calls and events; however we all hope this won’t always be necessary. We tread a fine line between showcasing and siloing the voices of women. But for now, concerts such as this introduce us to the works of composers from across the world which we might otherwise never have had a chance to hear. I can only now hope to see them integrated into our regular programming.

Below I explore some threads that tie together three of the works in the programme – my own LIT, Rhona Clarke’s Con Coro, and American composer Judith Shatin’s Gregor’s Dream– and the composers’ different approaches to exploring some of the same questions, such as the relationship between live and electronic, physical and intangible, music and literature, real and unreal.

LIT (for voice and electronics)

LIT is a work for voice and electronics that explores light and shadow, based on the poem of the same name by American poet Robert Fitterman, commissioned by Michelle O’Rourke with funds from Arts Council Ireland.

The imagery of this wonderful poem conjures textures of light and shade; as the opening says “Each section outlined below is an independent treatise on a limited aspect of light and colour”. From “crisp shadows and sculpted beams”, “pulsating codes of shine”, to being “lost in a world of sunlight”, or the colour of a “magnesium flare”, the text is rich in imagery of the physical and metaphorical manifestations of light.

For Fitterman, the poem has an inherently musical quality beyond that of the curated sounds of the text itself; in the words of the poet, it is “composed of samples from a range of sources-- poetry, science, etc.--that use the word ‘light’.” The musical work is open-form, built of discrete cells of these stand-alone images, textures and gestures that reflect the similar structure of the poem.

The poem’s text was composed “with both visual and aural emphasis”, the "black ink and white spaces” of the text on the page “echo[ing] themes of light and sound”. The poem then exists on a number of planes simultaneously, as it blurs the lines between a work as ‘script’ or ‘score’: as described by Nelson Goodman in Languages of Art(and as further discussed in Tim Ingold’s Lines), the first refers to the work itself, the second to a class of instructions to be realised. LIT the poem,exists as a written text, and also as a physical, visual object. It poses the question of where we locate the essence of ‘work’ of art (whether musical, literary or visual), in its realisation, or in its concept? Which is the reality, and which is the shadow?

My work explores similar themes: the relationship between score and performance, between performer, composer and audience – and above all, how can we truly communicate the essence of an idea of a textual work musically. Like LIT the poem, LIT the musical work also exists as both script and score: it is simultaneously a set of instructions for performance, the resulting aural work itself and a visual script that exists independently of its realisation.

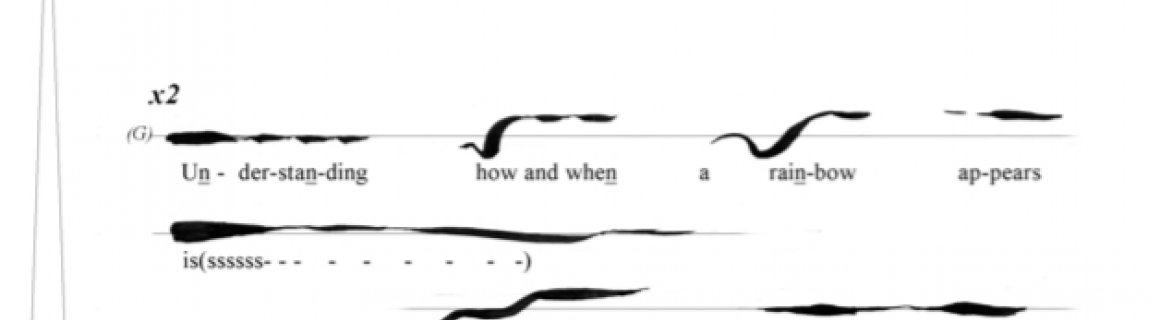

Visually, LIT reflects the black ink and white spaces through a gestural ink-stroke notational system, inspired by the ink paintings of China and Japan, and by the musical gestures of traditional music such as that of Noh theatre. The shape and thickness of the stroke indicates intensity and phrasing, while rhythm/duration are indicated by stroke length and relative positioning, though the piece is quite free. In the words of Yuehping Yen, calligraphers “observe the principles of every type of movement and rhythm and try to convey them through the calligraphic brush”.In LIT, each trace of the physical movement of the brush speaks a musical gesture, and vice versa.

Anna Murray, LIT - score excerpt:

Aurally, this manifests as a set of discrete musical gestures – the “black ink” – against a backdrop of both live and pre-recorded electronics, constructed from pre-recorded vocal pitches – the “white spaces”. The whole work then, as aural realisation, score and script, has light and shade in its structure, imagery and sound. And at the heart of it is the voice, the “reading out loud” that brings the work from the metaphysical into the physical.

Con Coro (for violin, cello and electronics)

Rhona Clarke’s Con Coro (“with choir”), as the name suggests, also holds the voice at its heart. However, in contrast to LIT, its focus is in entirely on the aural – to the literal exclusion of the visual (for its first performance, at the Rubicon Gallery the audience was blindfolded). And yet we find a connection, in the light and shadows created, and in the blurring of the blank page (the tape) and the black ink (the live instruments), reality and unreality.

In this case the tape is based on Clarke’s own voice, singing an extract of the plainchant Ubi Caritas:

“Ubi caritas et amor, Deus ibi est….

Simul ergo cum in unum congregamur:

Ne nos mente dividamur, caveamus

(Where charity and love are, God is there…

As we are gathered into one body, Beware,

Lest we be divided in mind).”

In Con Coro, the instruments and voice fight to be gathered into one, against being “divided in mind".

The heavily-processed voice exists only in its reverberation – it is just a shadow of a real voice. Even within the samples, we hear its own echos (the repeated “Deus” of the opening section, b.8/9, or the lingering, disassociated sibilance of b.14/15). A cello too, exists in this shadowy plane, a repeated, distorted ostinato – and immediately are we presented with the question of what is real and what is not, as the violin enters, playing a juddering repeated D# at the exact same time as the first unprocessed cello note in the tape, a B (b.7).

Rhona Clarke, Con Coro - score excerpt:

This first entry of violin and unprocessed anchors the real in a major 3rd, yet this is undermined by the persistent G# in the tape, itself further muddied by the memory of a lower E. Where are we situated as we listen, do we hear the major or the minor, the ‘one body’ or the ‘divided minds’? Especially for a blindfolded audience, the spatial separation of the real and the shadow is further confused; the space itself is dissolved. Now removed of both its visual and spatial dimensions, we are situated in a new space, where the light and the shadow swirl about one another, sometimes supporting, sometimes undermining.

Throughout Con Coro we are presented with these moments of presence and dissolution, lights shone and shadows cast. Sometimes harmonic, sometimes textural, sometimes spatial, there is a process of challenge, metamorphosis, and re-embodying.

Con Coro - Rhona Clarke

Gregor’s Dream (for amplified piano trio and electronics)

The ghostly shadow voice of Con Coro and LIT are replaced by those of beetles in Judith Shatin’s Gregor’s Dream – the manifestation of the ‘horrible bug’ of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, referenced in the work’s title.

Gregor’s Dreamtoo is a work of duelling realities: both literal and symbolic, a literary and aural metamorphoses. As in the original Kafka, the presence of the insects is symbolic, and like in Clarke’s Con Coro, processed so that they are shadows of the physical sources. In her programme notes, Shatin even names these beetles, the Asian Longhorn beetles (Anoplophora glabripennis) and mountain pine beetles (D. ponderosae, Ips pini and D. valens), setting up the duality between the specificity of the real entities, and the disembodied aural counterparts.

Significantly, the relationship between the live instruments and the chittering and droning of the insects is different to that of either LITor Con Coro. In LIT, the two elements are one, the white and black of text on a page; in Con Coro, the lines of reality are blurred; in Gregor’s Dream, the two respond to one another organically, though both remain ‘other’. Both human and insect are trapped in the same dream, and trapped in a spiral of fear and distrust.

Shatin treats these sounds like an obsession: they are constant, drilling, informing our understanding of everything that is placed against them. They are the nagging itch at the back of the work’s brain, and the basis for the disturbing claustrophobia at the heart of this aural realisation of Kafka’s literary work.

Throughout the piece, the instruments interject against this sawing noise, such as the stabbing plucked piano strings of the first entry (0.13) against a low, almost subterranean rumbling, or overtly melodic gestures that contrast against the alien insect sounds (9.17). Sometimes, they try to cajole the insects, to speak their language, with tremolo chitterings and creakings of their own (6.00), or harmonising held notes (8.15).

Inevitably, however, this fails, the ‘other’ remains other, and each return to their own language, though changed by their attempt to communicate.

Gregor’s Dream - Judith Shatin

LIT, Con Coroand Gregor’s Dreamwill all feature as part of the IAWM annual concert at Trinity College Chapel on Saturday, 27thOctober (full programme below), performed by Michelle O’Rourke and Kirkos Ensemble. The IAWM annual concert will be presented in partnership with The Contemporary Music Centre, Association of Irish Composers, Music Composition Centre at Trinity College Dublin, Music and Media Technologies Trinity College Dublin and the Royal Irish Academy of Music.

Programme:

Diane Berry - Calling

Rhona Clarke - con coro

Silvia Rosani - Die Elbe

Esther Shuyue Cao - Flashback

Amy Brandon - gestures of recoil

Judith Shatin - Gregor's Dream

Cara Haxo - Im Harren

Anna Murray - LIT

Anna Rubin - Songs to Death

Kelly-Marie Murphy - The Book of Elegant Feelings

Jane O'Leary - Winter Sketchbook

Tickets cost €8/€5 (students) + booking fee and are available here